A World of Art 8th Edition Chapter 18

WORLD OF ART EIGHTH EDITION CHAPTER 25 The Individual and Cultural Identity World of Art, Eighth Edition Henry M. Sayre Copyright © 2016, 2013, 2010 by Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliates. All rights reserved.

Learning Objectives 1. Define nationalism and describe how the arts have been used to construct and critique national identities. 2. Describe how the visual signs of class inform works of art. 3. Discuss racial identity as it manifests itself in African-American art.

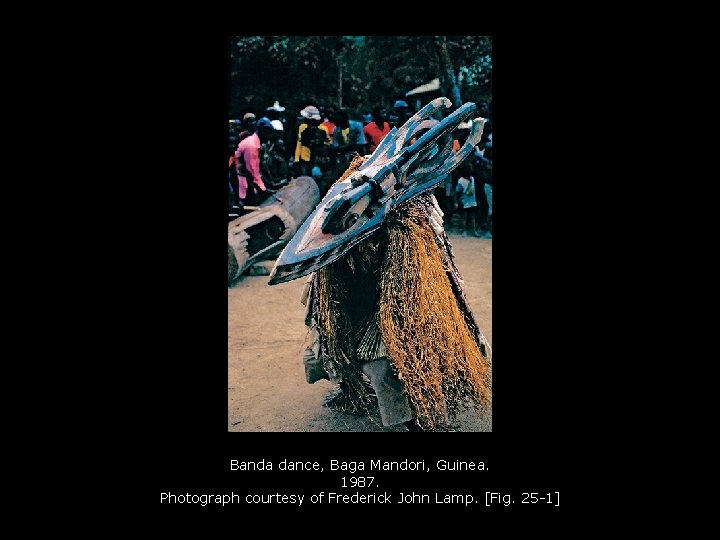

Introduction 1 of 2 • Gender plays an important role in the formation of identity, as does ethnic/class distinctions, as well as social and political allegiances to community and state. • The masked dance is a ritual activity universally practiced from one culture to the next.

Introduction 2 of 2 • It unites the creative efforts of sculptors, dancers, musicians, etc. • The banda mask is used by the Baga Mandori people who live on the Atlantic coastline of Guinea. § This is usually performed at night, but for the sake of creating a photographic record, villagers agreed to perform it at dusk.

Banda dance, Baga Mandori, Guinea. 1987. Photograph courtesy of Frederick John Lamp. [Fig. 25 -1]

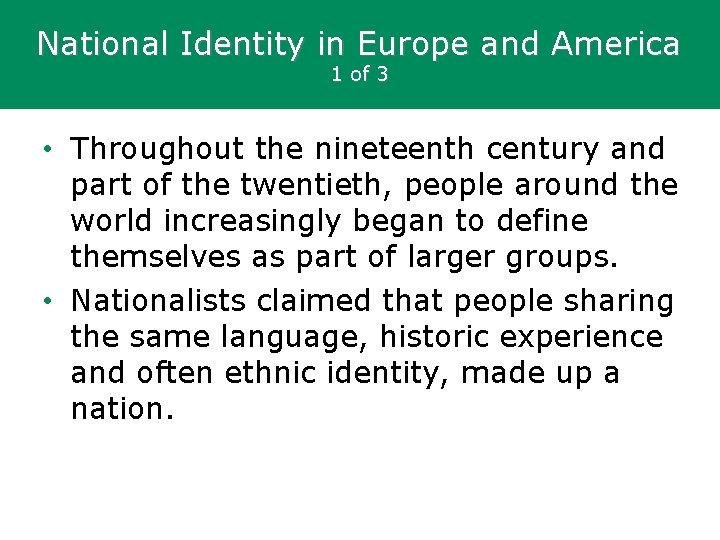

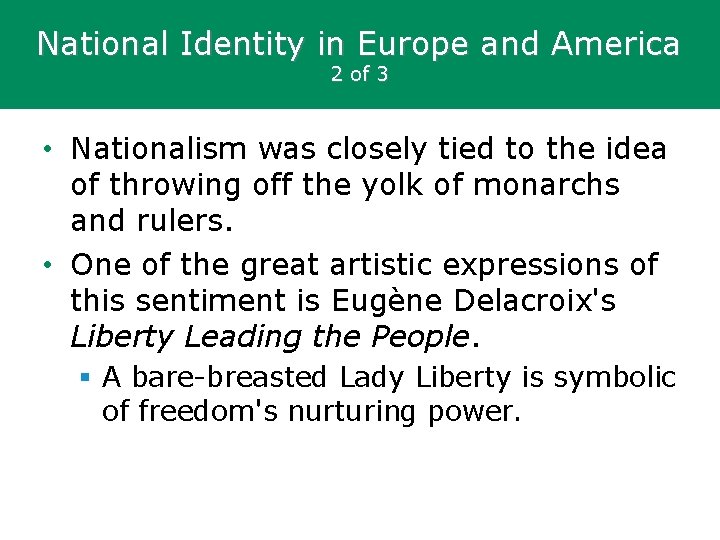

National Identity in Europe and America 1 of 3 • Throughout the nineteenth century and part of the twentieth, people around the world increasingly began to define themselves as part of larger groups. • Nationalists claimed that people sharing the same language, historic experience and often ethnic identity, made up a nation.

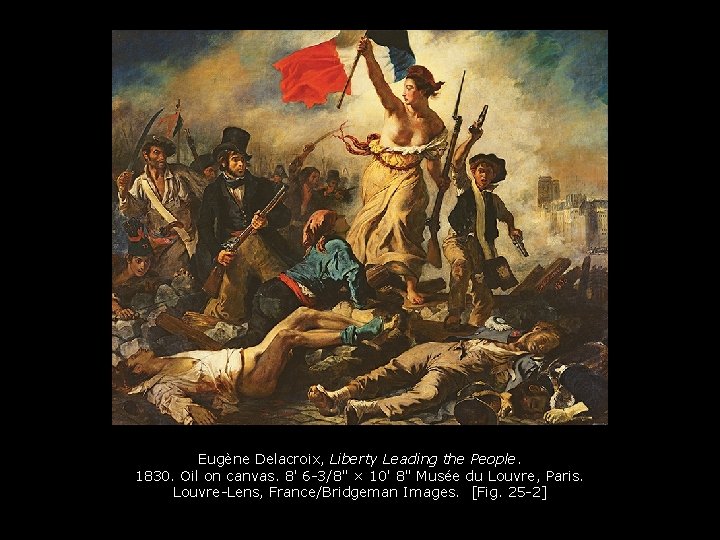

National Identity in Europe and America 2 of 3 • Nationalism was closely tied to the idea of throwing off the yolk of monarchs and rulers. • One of the great artistic expressions of this sentiment is Eugène Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People. § A bare-breasted Lady Liberty is symbolic of freedom's nurturing power.

Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People. 1830. Oil on canvas. 8' 6 -3/8" × 10' 8" Musée du Louvre, Paris. Louvre-Lens, France/Bridgeman Images. [Fig. 25 -2]

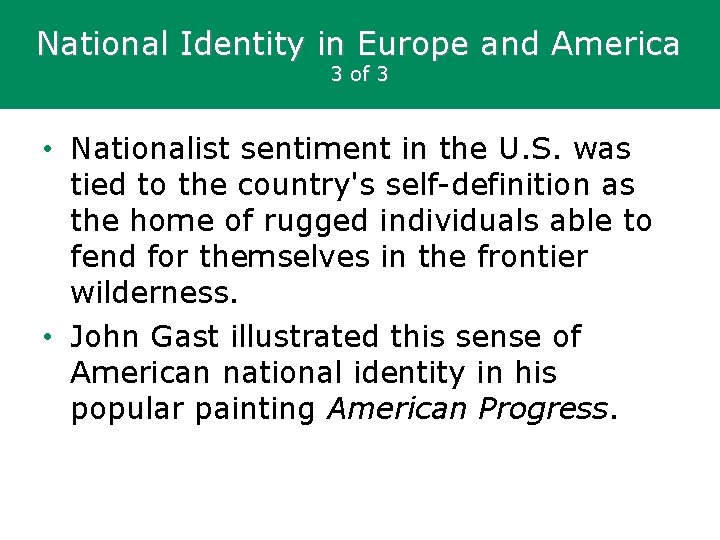

National Identity in Europe and America 3 of 3 • Nationalist sentiment in the U. S. was tied to the country's self-definition as the home of rugged individuals able to fend for themselves in the frontier wilderness. • John Gast illustrated this sense of American national identity in his popular painting American Progress.

John Gast, American Progress. 1872. Oil on canvas. 20 -1/4 × 30 -1/4" Private collection. Photo © Christie's Images/Bridgeman Images. [Fig. 25 -3]

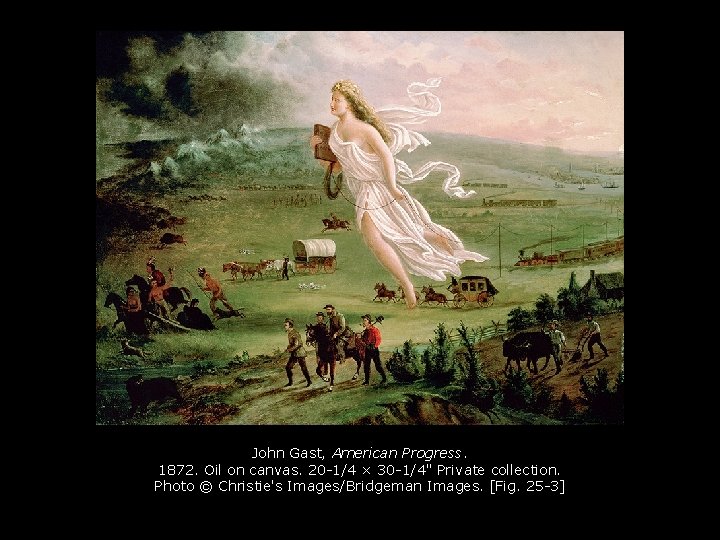

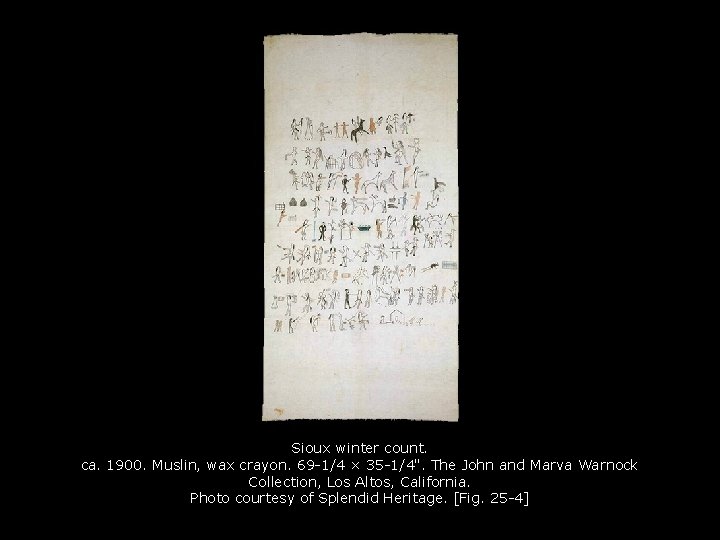

Native American Tribal History and Identity 1 of 2 • Native Americans self-identify as a group insofar as they can trace their ancestry to pre-contact peoples. • They share the common history of their conquest, but the songs, stories, and dances passed down through the generations are largely unique to each.

Native American Tribal History and Identity 2 of 2 • The Native Americans of the Great Plains, unlike many other tribes, recorded their history in copious detail. • Humans are generally stick figures, and events are described in selective detail. • Some tribes, particularly the Lakota Sioux and Kiowa, recorded family or band history in what is known as a "winter count. "

Sioux winter count. ca. 1900. Muslin, wax crayon. 69 -1/4 × 35 -1/4". The John and Marva Warnock Collection, Los Altos, California. Photo courtesy of Splendid Heritage. [Fig. 25 -4]

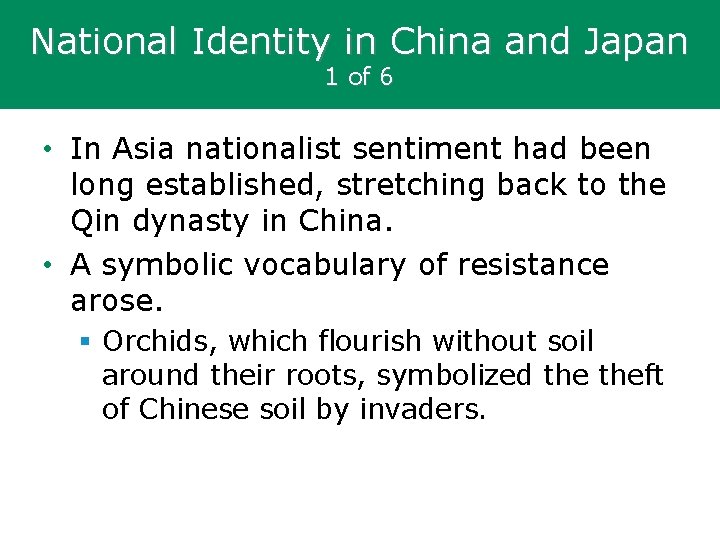

National Identity in China and Japan 1 of 6 • In Asia nationalist sentiment had been long established, stretching back to the Qin dynasty in China. • A symbolic vocabulary of resistance arose. § Orchids, which flourish without soil around their roots, symbolized theft of Chinese soil by invaders.

National Identity in China and Japan 2 of 6 • A symbolic vocabulary of resistance arose. § Bamboo represented flexibility, the quality that allows it to bend but not break. § Pine, which can grow in poor, rocky soil signified cultural survival. § Plum, which blooms in winter despite the harsh conditions, stood for perseverance in the face of adversity.

Ke Jiusi, Bamboo, after Wen Tong, Yuan dynasty. 1343. Hanging scroll, ink on silk. 42 -3/8 × 18 -3/4" Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. ex coll. : C. C. Wang Family, Gift of Oscar L. Tang Family, 2006. 571. © 2015. Image copyright Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence. [Fig. 25 -5]

National Identity in China and Japan 3 of 6 • During the Yuan dynasty of the Mongol conquerors, these became the very symbols of Chinese national identity. • The Japanese were even more protective of their identity. • Christianity, even as practiced by foreigners, was banned altogether in 1614.

National Identity in China and Japan 4 of 6 • In 1635, the Japanese were forbidden to travel abroad, and in 1641 foreign trade was limited to the Dutch. • Japan would remain sealed from foreign influence until 1853, when the American commodore Matthew Perry sailed in with four warships and a letter from the president of the U. S. urging Japan to receive the American sailors.

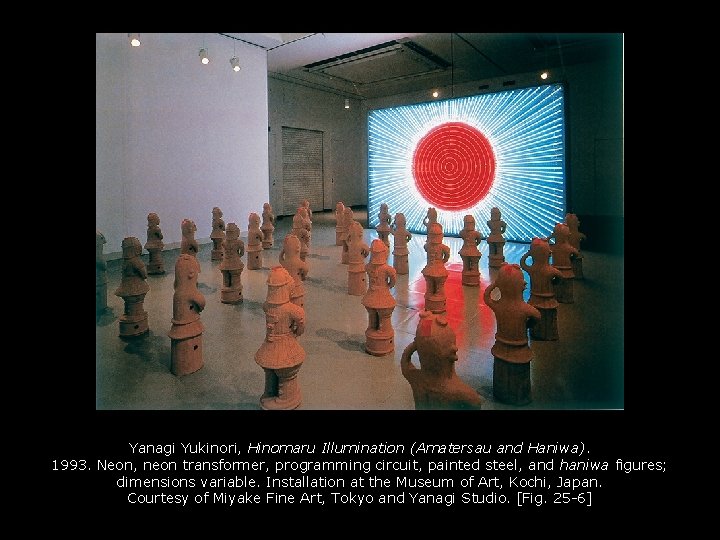

National Identity in China and Japan 5 of 6 • But a strong sense of national identity was firmly established, and it resulted, in an aggressive nationalism designed to assert Japan's preeminence in Asia. • This penchant for nationalist feeling in Japan began to reemerge in the 1980 s with Japan's rise as a commercial powerhouse built on technological innovation.

National Identity in China and Japan 6 of 6 • It inspired Yanagi Yukinori to create an installation titled Hinomaru Illumination (Amaterasu and Haniwa). • The haniwa here represent the Japanese people who blindly pay obeisance to those in power.

Yanagi Yukinori, Hinomaru Illumination (Amatersau and Haniwa). 1993. Neon, neon transformer, programming circuit, painted steel, and haniwa figures; dimensions variable. Installation at the Museum of Art, Kochi, Japan. Courtesy of Miyake Fine Art, Tokyo and Yanagi Studio. [Fig. 25 -6]

Class and Identity • In industrialized societies, economic status played a large role in determining a person's identity. • People came to identify themselves in terms of class.

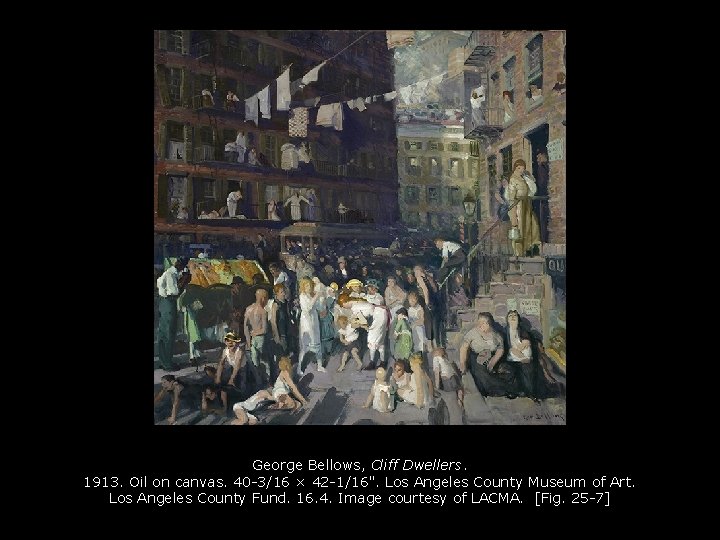

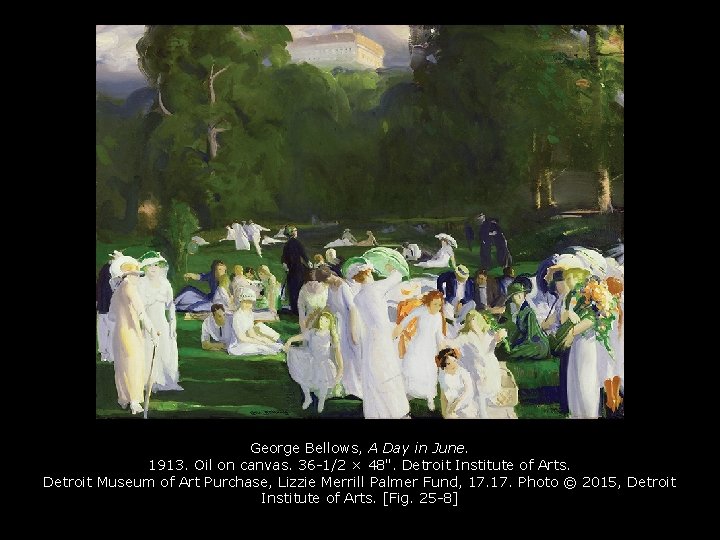

Making Class 1 of 4 • Visual clues often allow us to determine a person's class. • In 1913, when George Bellows painted the two works that were set in New York City, which was one of the most class-conscious cities in the world. § Cliff Dwellers showed the poor foreigners living in the city, while A Day in June showed the wealthy enjoying a day in the park.

George Bellows, Cliff Dwellers. 1913. Oil on canvas. 40 -3/16 × 42 -1/16". Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Los Angeles County Fund. 16. 4. Image courtesy of LACMA. [Fig. 25 -7]

George Bellows, A Day in June. 1913. Oil on canvas. 36 -1/2 × 48". Detroit Institute of Arts. Detroit Museum of Art Purchase, Lizzie Merrill Palmer Fund, 17. Photo © 2015, Detroit Institute of Arts. [Fig. 25 -8]

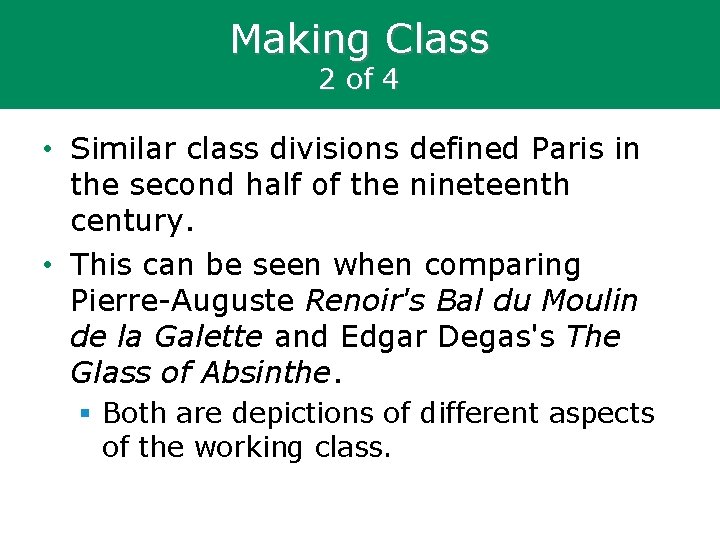

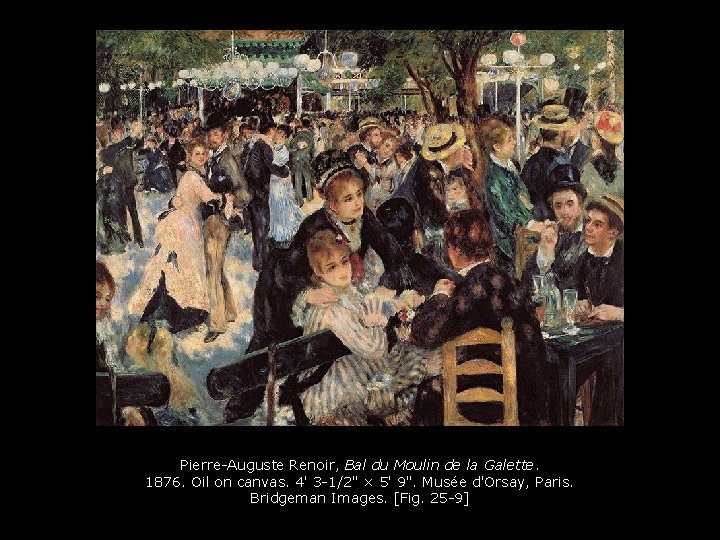

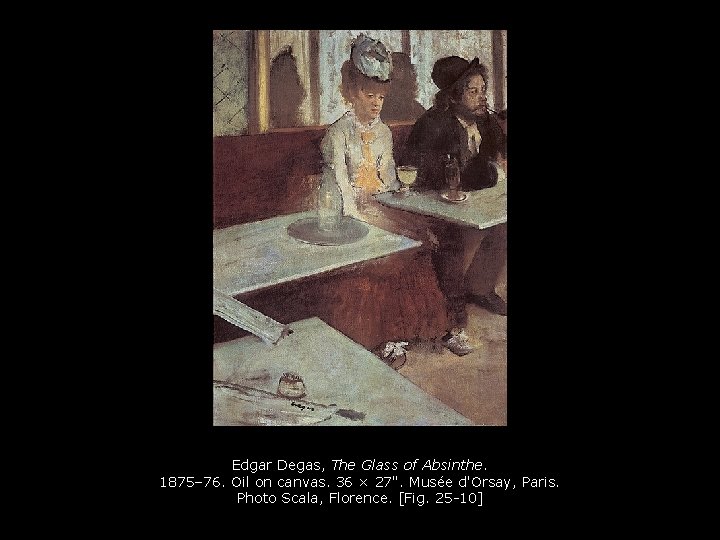

Making Class 2 of 4 • Similar class divisions defined Paris in the second half of the nineteenth century. • This can be seen when comparing Pierre-Auguste Renoir's Bal du Moulin de la Galette and Edgar Degas's The Glass of Absinthe. § Both are depictions of different aspects of the working class.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Bal du Moulin de la Galette. 1876. Oil on canvas. 4' 3 -1/2" × 5' 9". Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Bridgeman Images. [Fig. 25 -9]

Edgar Degas, The Glass of Absinthe. 1875– 76. Oil on canvas. 36 × 27". Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Photo Scala, Florence. [Fig. 25 -10]

Making Class 3 of 4 • Renoir masks their origins, dressing them in the bright fashions of the day and bringing them into the world of his intellectual friends as if they belonged there. • Degas's is indoors and closed-in, its figures isolated in their thoughts.

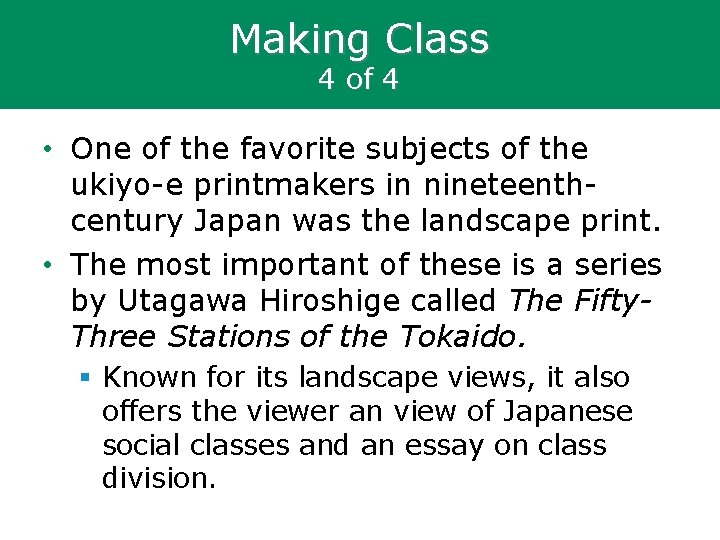

Making Class 4 of 4 • One of the favorite subjects of the ukiyo-e printmakers in nineteenthcentury Japan was the landscape print. • The most important of these is a series by Utagawa Hiroshige called The Fifty. Three Stations of the Tokaido. § Known for its landscape views, it also offers the viewer an view of Japanese social classes and an essay on class division.

Utagawa Hiroshige, Hamamatsu: Winter Scene, plate 30 from The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido, Hoeido edition. 1831– 34. Woodblock print. 9 -7/8 × 14 -3/4". Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, U. K. Art Archive/Ashmolean Museum. [Fig. 25 -11]

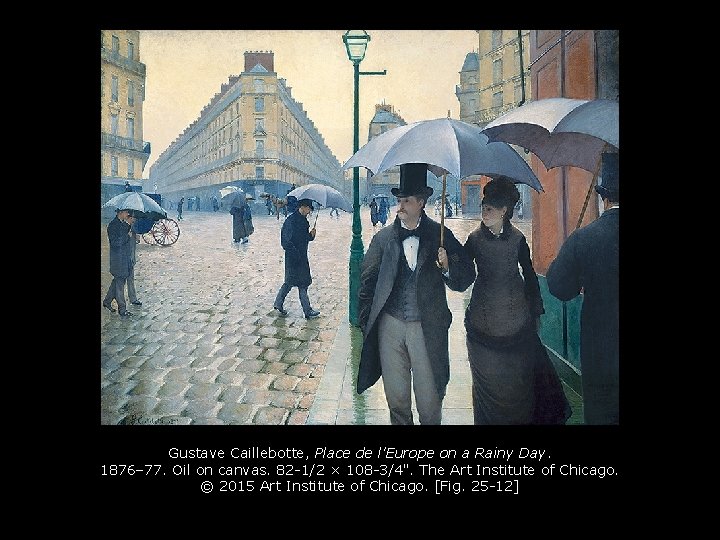

Place and Displacement 1 of 6 • The broad, open avenues in Gustave Caillebotte's painting Place de l'Europe on a Rainy Day were the result of what has come to be known as the Haussmannization of Paris. • Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann was tasked with planning the modernization of Paris by destroying the old city and rebuilding it.

Gustave Caillebotte, Place de l'Europe on a Rainy Day. 1876– 77. Oil on canvas. 82 -1/2 × 108 -3/4". The Art Institute of Chicago. © 2015 Art Institute of Chicago. [Fig. 25 -12]

Place and Displacement 2 of 6 • The goal was to rid Paris of its medieval character, transforming it into the most beautiful city in the world—and to prevent the possibility of uprisings again like that depicted in Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People.

Place and Displacement 3 of 6 • The destruction of working-class neighborhoods throughout Paris was the price the city paid for this transformation. • It resulted in a city inhabited almost exclusively by the bourgeoisie and upper-class citizens.

Place and Displacement 4 of 6 • Paris became a city of leisure, surrounded by a ring of industrial and working-class suburbs, and it remains so today. • Since the early 1980 s, Beijing has undergone a transformation similar to Haussmann's transformation of Paris.

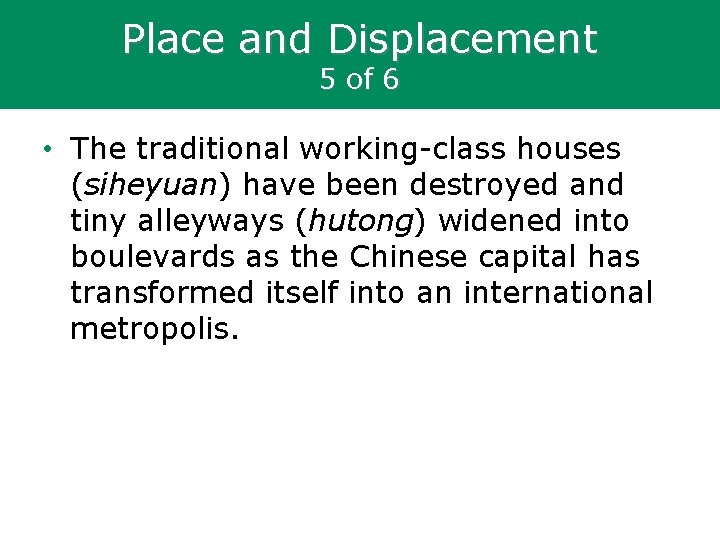

Place and Displacement 5 of 6 • The traditional working-class houses (siheyuan) have been destroyed and tiny alleyways (hutong) widened into boulevards as the Chinese capital has transformed itself into an international metropolis.

![Aerial view of old hutong area, Beijing. © Radius Images/Corbis. [Fig. 25 -13] Aerial view of old hutong area, Beijing. © Radius Images/Corbis. [Fig. 25 -13]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/e823ae3d2ba0ccde853385de3813a9d6/image-38.jpg)

Aerial view of old hutong area, Beijing. © Radius Images/Corbis. [Fig. 25 -13]

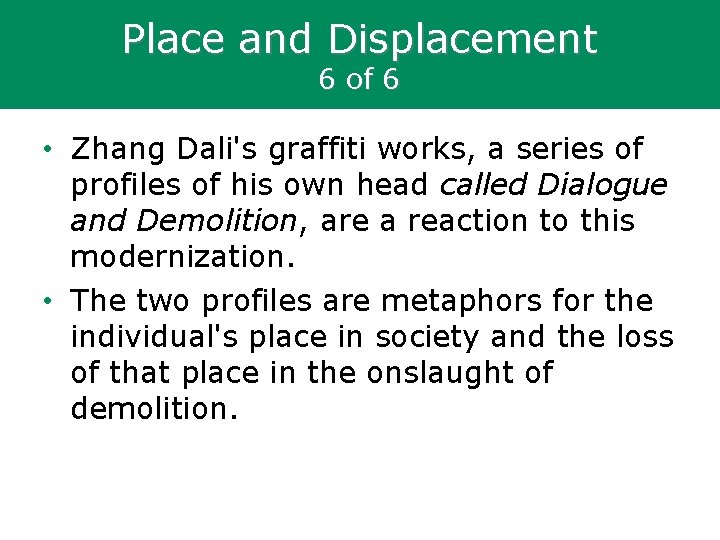

Place and Displacement 6 of 6 • Zhang Dali's graffiti works, a series of profiles of his own head called Dialogue and Demolition, are a reaction to this modernization. • The two profiles are metaphors for the individual's place in society and the loss of that place in the onslaught of demolition.

Zhang Dali, Dialogue and Demolition No. 50. 1998. Photograph. 23 -5/8 × 35 -3/8". Klein Sun Gallery, New York. Courtesy of Klein Sun Gallery, Zhang Dali. [Fig. 25 -14]

Racial Identity and African-American Experience 1 of 2 • Western culture has tended to associate blackness with negative qualities and whiteness with positive ones. • In "Race"ing Sideways, Nikolai Buglaj has 13 racers tied for the lead in a race no one seems intent on winning. § This equality is an illusion.

Racial Identity and African-American Experience 2 of 2 • In "Race"ing Sideways, Nikolai Buglaj has 13 racers tied for the lead in a race no one seems intent on winning. § It comments on the lack of progress we have made in race and class relations in this country.

![Nikolai Buglaj, "Race"ing Sideways. 1991. Graphite and ink. 3 × 40". [Fig. 25 -15] Nikolai Buglaj, "Race"ing Sideways. 1991. Graphite and ink. 3 × 40". [Fig. 25 -15]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/e823ae3d2ba0ccde853385de3813a9d6/image-43.jpg)

Nikolai Buglaj, "Race"ing Sideways. 1991. Graphite and ink. 3 × 40". [Fig. 25 -15]

Double Consciousness and the Great Migration 1 of 5 • Progress has been the driving force of the Civil Rights Movement since the beginning of the twentieth century.

Double Consciousness and the Great Migration 2 of 5 • From 1915 through 1918, between 200, 000 and 350, 000 Southern blacks moved north in what came to be called the Great Migration. § Transformed from field hands into industrial laborers, these migrants faced a real crisis in self-definition.

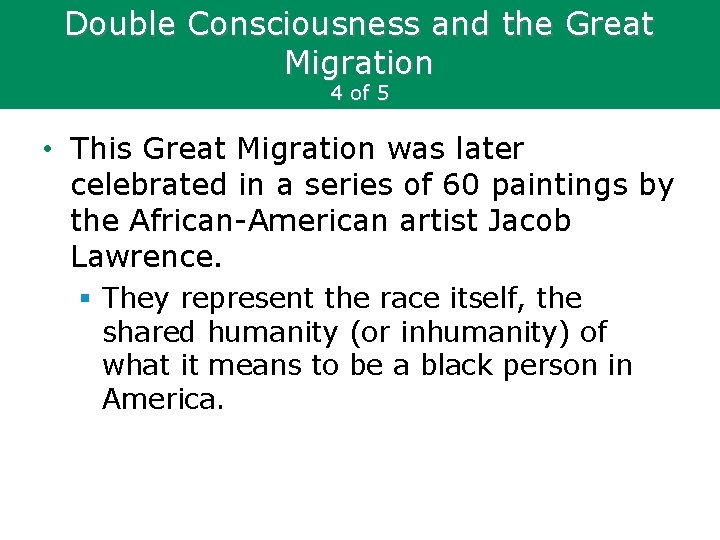

Double Consciousness and the Great Migration 3 of 5 • This Great Migration was later celebrated in a series of 60 paintings by the African-American artist Jacob Lawrence. § Throughout the series, Lawrence's figures are almost faceless, twodimensional silhouettes, possessing almost no individuality.

Double Consciousness and the Great Migration 4 of 5 • This Great Migration was later celebrated in a series of 60 paintings by the African-American artist Jacob Lawrence. § They represent the race itself, the shared humanity (or inhumanity) of what it means to be a black person in America.

Jacob Lawrence, The Migration of the Negro, Panel No. 60: And the Migrants Kept Coming. 1940– 41. Casein tempera on hardboard panel. 18 × 12". Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Ms. David M. Levy, 28. 1942. 30. Digital image, Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence. © 2015 Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. [Fig. 25 -16]

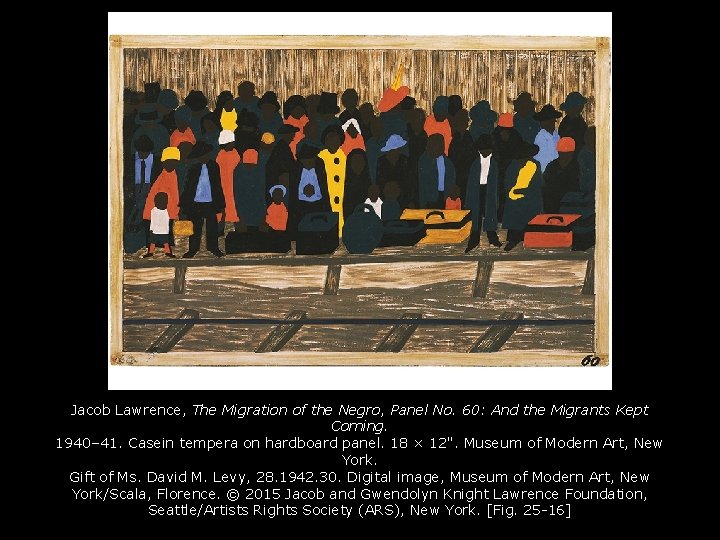

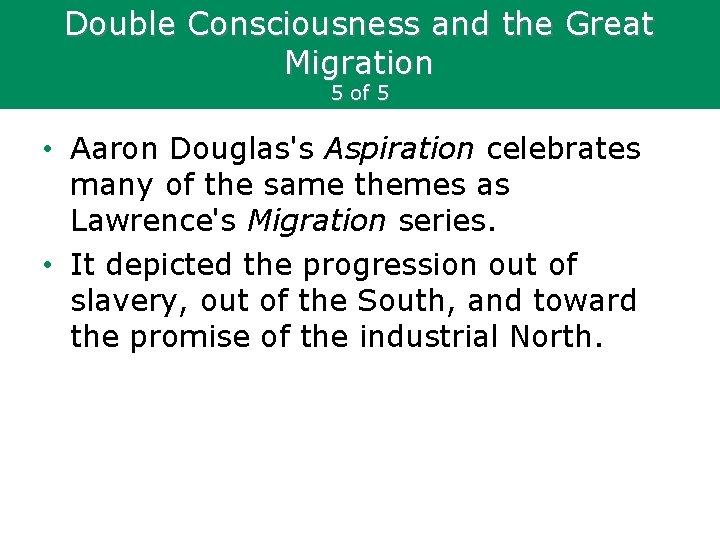

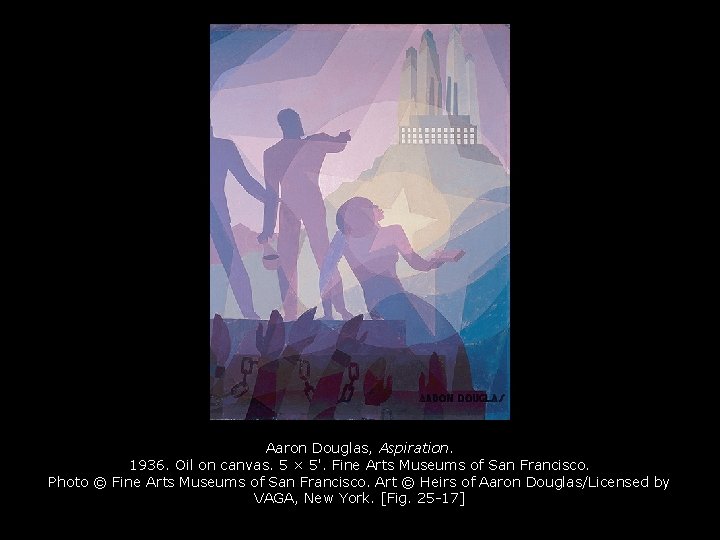

Double Consciousness and the Great Migration 5 of 5 • Aaron Douglas's Aspiration celebrates many of the same themes as Lawrence's Migration series. • It depicted the progression out of slavery, out of the South, and toward the promise of the industrial North.

Aaron Douglas, Aspiration. 1936. Oil on canvas. 5 × 5'. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Photo © Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Art © Heirs of Aaron Douglas/Licensed by VAGA, New York. [Fig. 25 -17]

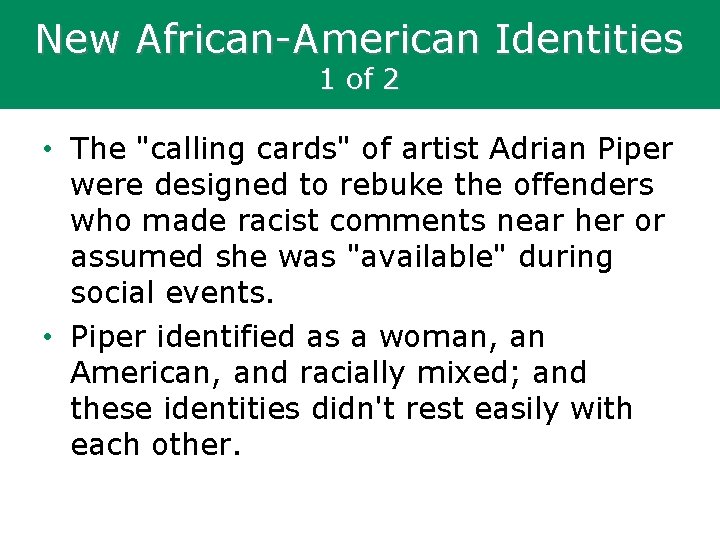

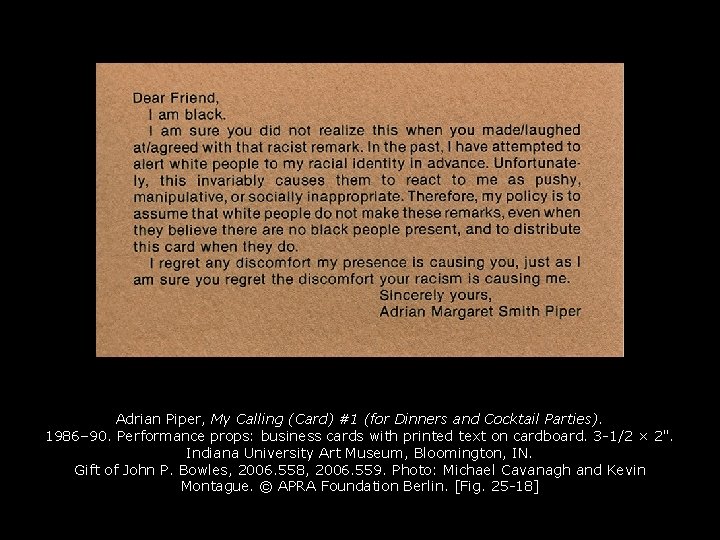

New African-American Identities 1 of 2 • The "calling cards" of artist Adrian Piper were designed to rebuke the offenders who made racist comments near her or assumed she was "available" during social events. • Piper identified as a woman, an American, and racially mixed; and these identities didn't rest easily with each other.

Adrian Piper, My Calling (Card) #1 (for Dinners and Cocktail Parties). 1986– 90. Performance props: business cards with printed text on cardboard. 3 -1/2 × 2". Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, IN. Gift of John P. Bowles, 2006. 558, 2006. 559. Photo: Michael Cavanagh and Kevin Montague. © APRA Foundation Berlin. [Fig. 25 -18]

Adrian Piper, My Calling (Card) #2 (for Bars and Discos). Performance props: business cards with printed text on cardboard, 3 -1/2 × 2". Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington, IN Gift of John P. Bowles, 2006. 558, 2006. 559. Photo: Michael Cavanagh and Kevin Montague. © APRA Foundation Berlin. [Fig. 25 -18]

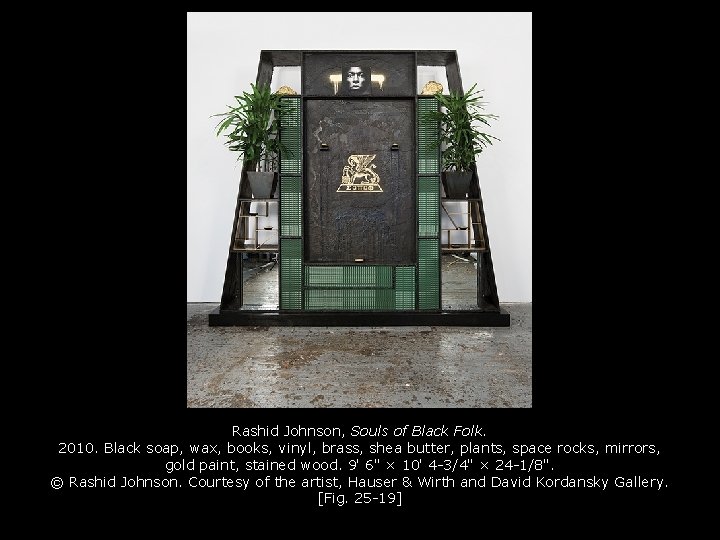

New African-American Identities 2 of 2 • Thelma Golden's exhibition Freestyle introduced the phrase "Post-Black" into the discussion—artists who were first and foremost artists and only secondarily black. • Rashid Johnson's shelf-like sculpture Souls of Black Folk—"a thing to put things on"—embodies just this "Post. Black" sensibility.

Rashid Johnson, Souls of Black Folk. 2010. Black soap, wax, books, vinyl, brass, shea butter, plants, space rocks, mirrors, gold paint, stained wood. 9' 6" × 10' 4 -3/4" × 24 -1/8". © Rashid Johnson. Courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth and David Kordansky Gallery. [Fig. 25 -19]

The Critical Process 1 of 4 • Thinking about the Individual and Cultural Identity § Flags were not commonly used as symbols of national identity until the eighteenth century. § Americans came to identify closely with their flag.

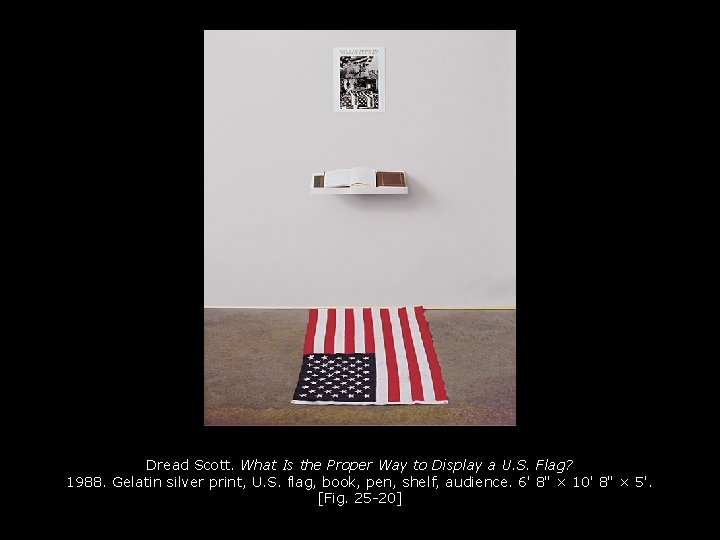

The Critical Process 2 of 4 • Thinking about the Individual and Cultural Identity § One of the most controversial works of art that has ever addressed the politics that surround the American flag is Dread Scott's What Is the Proper Way to Display a U. S. Flag?

The Critical Process 3 of 4 • Thinking about the Individual and Cultural Identity § It consisted of an American flag draped on the floor beneath photographs of flag -draped coffins and South Koreans burning the flag. § Beneath the photos was a ledger in which viewers were asked to record their opinions.

The Critical Process 4 of 4 • Thinking about the Individual and Cultural Identity § The problem was that the flag was on the floor, and that it was hard to write in the ledger without stepping on it. § Viewers had to choose which they revered more—the flag or freedom of speech.

Dread Scott. What Is the Proper Way to Display a U. S. Flag? 1988. Gelatin silver print, U. S. flag, book, pen, shelf, audience. 6' 8" × 10' 8" × 5'. [Fig. 25 -20]

Thinking Back 1. Define nationalism and describe how the arts have been used to construct and critique national identities. 2. Describe how the visual signs of class inform works of art. 3. Discuss racial identity as it manifests itself in African-American art.

A World of Art 8th Edition Chapter 18

Source: https://slidetodoc.com/world-of-art-eighth-edition-chapter-25-the/